Director: Alan J Pakula

Written by: David Giler, Lorenzo Semple Jr., Robert Towne (uncredited)

Based on the novel by: Loren Singer.

Alan J Pakula’s film stars Warren Beatty as a down-and-out journalist who stumbles across an international conspiracy, three years after the assassination of a popular US senator.

The 1970’s might have been a tumultuous decade for American politics, but there can be no argument that it also fostered some of the preeminent talents in American cinema. When you consider the sheer volume of singularly brilliant filmmakers to arrive on The New Hollywood roster, the sum of talent is overwhelming. Even omitting those who have passed away, or sadder still, chosen to retire, the catalog is rich:

Woody Allen, Steven Spielberg, Roman Polanski, Paul Schrader, Martin Scorsese, Ridley Scott, George Lucas, Clint Eastwood, William Friedkin, Francis Ford Coppola… These are all urgent filmmakers whose output has remained both interesting, and in-demand. Scorsese films are still event films. Scott films are still event films. Spielberg films are still are, and will always be, event films. It’s a testament to their collective expertise that these directors never fell off the radar, or lost touch with their medium.

You could say The Parallax view arrived at precisely the right time, or if you’d prefer, that historical events arrived at the right time for The Parallax View. Whatever your view, Pakula’s film is unmistakably a product of its era, invoking every 70s neurosis — from the Kennedy Hangover, to Watergate, and Vietnam — to generate its paranoid atmosphere.

I’m a big advocate of Pakula. I’ve got endless time for his filmography. Like many of his peers, chiefly Brian DePalma and Bill Friedkin (both of whom I also rate highly), Pakula’s Hitchcock line is generally on the surface. Tension is crafted with delicate attention, and subtextual terror is used to endow otherwise innocuous imagery with fresh foreboding.

There are several moments in the Parallax View which recall Hitchcock in this way, but one of the most memorable involves a stack of napkins.

Warren Beatty, our hero, has just boarded a plane in search of an elusive assassin, only to realise upon takeoff, that the perpetrator has fled — and left a time-activated bomb in the hold. Beatty is now tasked with alerting the crew, but must do everything in his power to avoid drawing their suspicion. After frantically scrambling for a way to communicate this warning, he eventually scrawls something onto a napkin, before slipping this missive onto a passing stewardess’ trolley. A tense, unbroken shot of the undisturbed napkin follows; as the stewardess continues down the aisle, offering drinks, oblivious to the note. The panic bubbles up as we watch and wonder: will she see it, will she disregard it, how will she react, will it be too late?

The film also benefits from an evocative, sinister soundtrack, courtesy of Michael Small, who worked memorably on films like Klute, and Marathon Man. His music trips all the right emotions, evoking a mixture of dread, dashed hope, paranoia, and cynicism, with its stirring drum cadence, and powerful, dissonant motif. I was reminded of John William’s JFK score, which for me, remains the heavyweight’s most simultaneously chilling, and rousing theme.

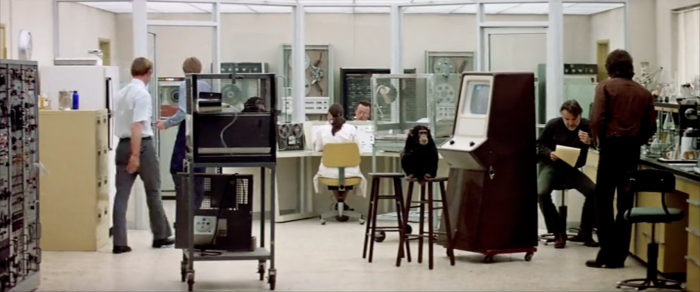

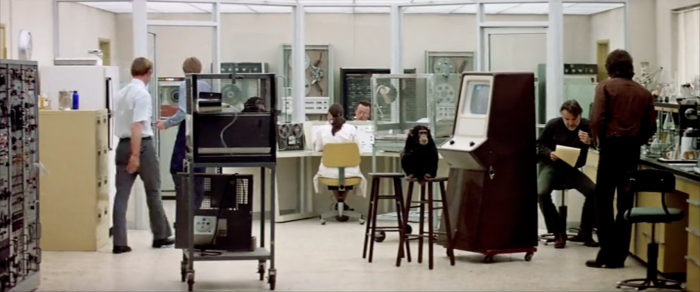

There comes, at around the film’s mid-way point, a tremendous, blind-sider sequence — in the form of an extended montage. Beatty has infiltrated the Parallax corporation (an extra-governmental group which moulds psychopaths into assassins, and, just occasionally, patsies) and is being forced to watch five minutes of ‘visual materials’ as part of their testing procedure. A slideshow of Images, punctuated by title-cards (‘MOTHER’, ‘FATHER’, ‘LOVE’, ‘ME’, ‘COUNTRY’), flicker over the screen at growing speed. As the presentation wears on, pictures swap into different groupings (sexual imagery appears in the ‘MOTHER’ category, and nazi rallies appear alongside Nixon in ‘COUNTRY’). This five minutes interlude remains both daring and electric to this day, capturing the viewer’s gaze like hypnotic propaganda. Its effect is so potent, that afterwards, audiences may well find themselves asking a difficult questions about the plasticity of emotion, allegiance, and free-will..

I would be remiss not to namecheck Soylent Green (released the same year as Parallax), for its virtuoso scenes of montage, all of which achieve, through comparable techniques, a similarly downbeat and nasty reaction. Also present are distinct grammatical similarities between this film, and later paranoid Sci-Fi fare like Logan’s Run, and Kaufman’s Body Snatchers remake, to name but a few.

I watched Parallax on Netflix’s streaming service, and spent a good deal of time poring over the various reviews, after the fact. Perhaps this was unwise. Despite the numerous positive notes, there was a depressing trend of misinformed conjecture. Cries of ‘hard to follow’, ‘pointless’, and most erroneously of all — ‘dumb’. This didn’t entirely surprise me, though it did leave me eager to rebut.

The Parallax View does not trace a particularly complex plot. Beat to beat, the story is brisk and linear, but unlike many contemporary offerings, it is told with a lavish, visually compelling style. The mis-en-scene, interior and exterior, is always precisely composed in super-wide 2:35:1 (this is illustrated in the pictures accompanying this review), however it’s the little details (napkins and such) that really elevate the piece — and I wouldn’t be surprised if it was precisely this focus on ‘detail’ that threw off the film’s latter-day detractors. They simply weren’t looking at the napkin, or the sack lunch (containing the poisoned sandwich), or the silver platter of drinks (which concealed the gun). No, instead they were elsewhere, waiting for the explosion.

General appetites have changed since 1974, favouring a blander, glossier product. This unfortunate depression in quality is likely the result of perennial, nervous, studio interference. After all, genre films can be volatile statements. Personally, I think this is their purpose. But challenging themes, a complex visual language, and open ended stories are no longer considered profitable. Studios like to neuter genre films.

It seems that, increasingly, modern thrillers rely on a handful of hoary tropes to placate audiences. A few examples of these, would be:

– Overwrought, uninspired, and typically superfluous chases — in which a constantly roaming and swinging camera, coupled with breakneck edits, flattens any spirit of tension.

– Loud pyrotechnics, usually achieved with glossy VFX, thrown in repeatedly and unimaginatively.

– All-too-frequent helicopter establishing shots (in case the audience forgot that cityscapes existed). These scenes are almost always accompanied by an ominous groan of music. God forbid one of these forms the film’s opening scene — there might not be a greater red flag…

For a meaningful comparison, take any number of modern paranoid thrillers — the Taylor Lautner Thriller Abduction, or Pierce Brosnan’s recent ‘Survivor’, do feel free to pick freely — and study their methods closely. There is nothing about these films, speaking particularly about their command of a visual language, which suggests any ability beyond low-functioning competency. No flair, no invention, no risk. The images tell a story, but do so in a flaccid, by-the-numbers style. Now return to Parallax, and take any one of its frames: they all mean something.

The worst part about all this, is that undiscerning viewers will often insist that a film like Abduction is the superior product. After all, it’s newer, there are more explosions, more cuts, and at no point do the filmmakers stop to interrogate the images on screen, or pose any challenging questions.

So, considering all of the aforementioned, it is perhaps understandable that a decent handful of people would miss the net here. And as I am loath to complain about the viewing habits of others (we’re all hypocrites in that respect, aren’t we?), I’ll curtail this rant for the time being. Though as a final word, I should express that I do find pleasure in a number of (relatively) new filmmakers in this genre — Denis Villeneuve to name but one. It’s certainly not all rotten apples.

The Parallax View is comfortably one of the quickest and most daring conspiracy thrillers of the 1970’s. Daring for its willingness to counter mainline notions about political process, and assert something seedier. It was controversial enough when Stone took this position in 1991, but he had nearly three decades of clearance — Pakula’s film had only one.

As the film posits: ‘there is a natural bureaucratic tendency to cover up mistakes’. Pakula is indicting the entire US government, if not for first degree murder, than at the very least for malfeasance.

S.S.